Roundabouts - Yarger Engineering, Inc. 317-475-1100 Email Us

Roundabouts

The most dangerous place on a road is often the signalized intersection. Roundabouts are great alternatives to signals and all-way stops, but they are not a cure all. Often they are much more expensive than a signal and require additional right-of-way be purchased. A roundabout can run $1,000,000 to $2,000,000 not including engineering, right-of-way and utility relocations. A signalized intersection with turn lanes may be half of that or less, and may fit within the existing right-of-way. Still, given the safety differences between a roundabout and signal, the roundabout can be the long term cheaper option when including the cost of crashes at a signal.

Runabouts are circular intersections, but not all circular intersections are roundabouts. Roundabouts generally have an outside diameter of 100 – 200 feet while traffic circles, also called rotories, may have outside diameters of 500 – 1,000 feet. On a roundabout, the circulating traffic on the circle has the right-of-way, and the approaches must yield to circulating traffic. On traffic circles, the traditional right of way rule for unsigned intersections applied so the circulating traffic had to yield to the traffic trying to enter, which filled up the circular roadway while reducing the exiting capacity. In modern roundabouts the exiting traffic has the right-of-way over vehicles trying to enter and only yields to pedestrians in the crosswalk.

Single Lane Roundabouts

Single lane roundabouts typically have an outside diameter of 125 to 150 feet with some being smaller and some being larger. They are designed with a free flow speed of 20 - 25 mph, and it is important to slow traffic before entering the roundabout with smaller turns on the approach. Older roundabouts did this primarily with just the splitter island and the first turn, but newer roundabouts tend to have a bit of a slalom on the approaches. The radii of the turns in a roundabout are also important as they are what enforces the design speed. A single lane roundabout can typically handle about 15,000 - 25,000 vehicles per day, but of course, this is dependent on the percentage of left turns and the hourly peaking since intersections are designed for the peak hour traffic, not daily traffic. At the conflict points within the roundabout, the capacity of the approach plus the circulating traffic is about 1,100 vehicles per hour. The video to the left was taken at the single lane roundabout to the right from the northwest corner during the 5:00 PM rush hour.

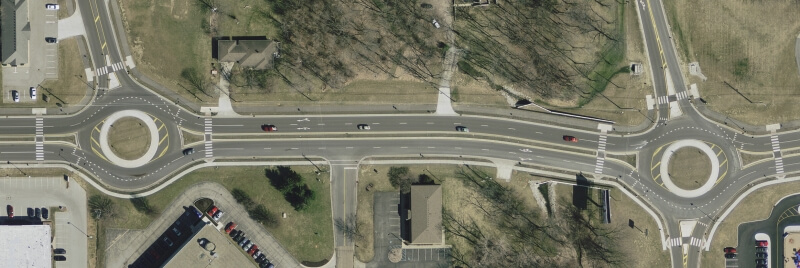

Multi-lane Roundabouts

Multi-lane roundabouts have one or more approaches with two approach lanes. The circulating road may have two or more lanes that go partially or completely around the center island. Like a single lane roundabout it is important to slow the speeds before entering the roundabout but the design speeds tend to be a bit higher. In order to prevent sideswipes the entering traffic needs to be turned and straightened back out to for a short distance so that the approach lanes are aligned with the appropriate circulating lanes. Existing lanes need to be marked as to which lanes may or must exit. In short, the right lane can’t continue around the roundabout if the left lane is allowed to exit. This can be shown in the roundabout with pavement markings such as dotted lines, solid lines and arrows.

Mini-Roundabouts and Neigborhood Traffic Circles

Mini-roundabouts and neighborhood traffic circles are terms used for a circular intersection that is smaller than a traditional roundabout, but lacks key elements. They may fit within the confines of a traditional intersection. The center island and the splitter islands may be mountabout or even paint so that larger vehicles can drive over them while cars can travel around the center island. In the photo to the right, the curbs are verticle, the approach lacks a splitter island, and the traffic is controlled as a two-way stop with stop signs on the side streets. It clearly isn't a roundabout, but it does function as a neighborhood traffic circle.

Pedestrians

Pedestrian paths at roundabouts are a bit of a circuitous route compared to a traditional intersection, but they break the crossing movements into smaller parts and often cross less lanes given the capacity of the intersection. The splitter island provides an opportunity for the pedestrian to cross one direction of traffic, and then wait for a break to cross the other direction. One downside of roundabouts, especially multiple lane roundabouts, is that they are more difficult for vision impaired pedestrians to crossing because the vehicle sounds are not oriented in a specific direction relating to the pedestrian paths. At a traditional intersection, most of the vehicles are going either north and south, or east and west which is easier to hear which way the traffic is going.

Bicycles

Bicycles at roundabouts should either act as a car and take the full lane in the roundabout, or act as a pedestrian and cross the roundabout in the crosswalks. Many urban roundabouts will have a ramp for the bicycle to enter and exit the sidewalk or multi-use paths. In no case should a bicycle lane be marked through the roundabout alongside a vehicle lane due to exiting vehicles crossing over the bike lanes.

Efficiency

Roundabouts tend to be more efficient, that is have less delay than traffic signals or all-way stops. During peak hours, the delay is a function of the design of the roundabout or signal since in either case the delay is going to be a function of the number of lanes; the big efficiency improvement that roundabouts have over signals is in the non-peak hours. During those hours a roundabout is also more equitable since the side street traffic doesn't have to wait on the signal to change.

Safety

Roundabouts are generally much safer than traditional intersections, primarily because of the operating speeds are lower and there are fewer conflicts. Overall number of crashes are reduced about 35%. The biggest safety gains are in injury crashes where injuries are reduced about 75%. Single lane roundabouts tend to be safer than multi-lane roundabouts. See NCHCP Report 672 chapter 5 for more information on roundabout safety.

When to Install

Roundabouts shouldn’t be installed everywhere since they are costly, but they should be considered as an alternative anytime a new intersection is created. Another good time to consider them is when there is a congestion problem at an existing intersection and traffic signal or multiple way stop warrants are satisfied. Roundabouts tend to work better with equal flows on the various legs and there is sufficient storage between intersections. When there is insufficient downstream storage, the roundabout can lock up because circulating vehicles can't leave the roundabout.

MUTCD

Roundabouts are regulated by the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) which controls how they are signed and marked. Unlike signals and all-way stops, the MUTCD does not have warrants for when a roundabout may be installed. Each state has its own version or adopts the federal version. See Indiana MUTCD or Federal MUTCD.

Costs

Generally roundabouts require a complete reconstruction of the intersection. When combined with high design standards such as those used by state DOTs a roundabout can cost $1,000,000 to $2,000,000. Smaller local roundabouts can cost less, but still should be thought of as costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. These costs can offset the cost of a traditional intersection modification where multiple turn lanes and traffic signals can also cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Key Features (Table from NCHRP Report 672 Exhibit 1-2)

| Central Island | The central island is the raised area in the center of a roundabout around which traffic circulates. The central island does not necessarily need to be circular in shape. In the case of mini-roundabouts the central island is traversable. |

| Splitter Island | A splitter island is a raised or painted area on an approach used to separate entering from exiting traffic, deflect and slow entering traffic, and allow pedestrians to cross the road in two stages. |

| Circulatory Roadway | The circulatory roadway is the curved path used by vehicles to travel in a counterclockwise fashion around the central island. |

Apron |

An apron is the traversable portion of the central island adjacent to the circulatory roadway that may be needed to accommodate the wheel tracking of large vehicles. An apron is sometimes provided on the outside of the circulatory roadway. |

| Entrance Line | The entrance line marks the point of entry into the circulatory roadway. This line is physically an extension of the circulatory roadway edge line but functions as a yield or give-way line in the absence of a separate yield line. Entering vehicles must yield to any circulating traffic coming from the left before crossing this line into the circulatory roadway. |

| Accessible Pedestrian Crossings | For roundabouts designed with pedestrian pathways, the crossing location is typically set back from the entrance line, and the splitter island is typically cut to allow pedestrians, wheelchairs, strollers, and bicycles to pass through. The pedestrian crossings must be accessible with detectable warnings and appropriate slopes in accordance with ADA requirements. |

| Landscape Strip | Landscape strips separate vehicular and pedestrian traffic and assist with guiding pedestrians to the designated crossing locations. This feature is particularly important as a wayfinding cue for individuals who are visually impaired. Landscape strips can also significantly improve the aesthetics of the intersection. |

See NCHCP Report 672 for a lot more information on roundabouts.

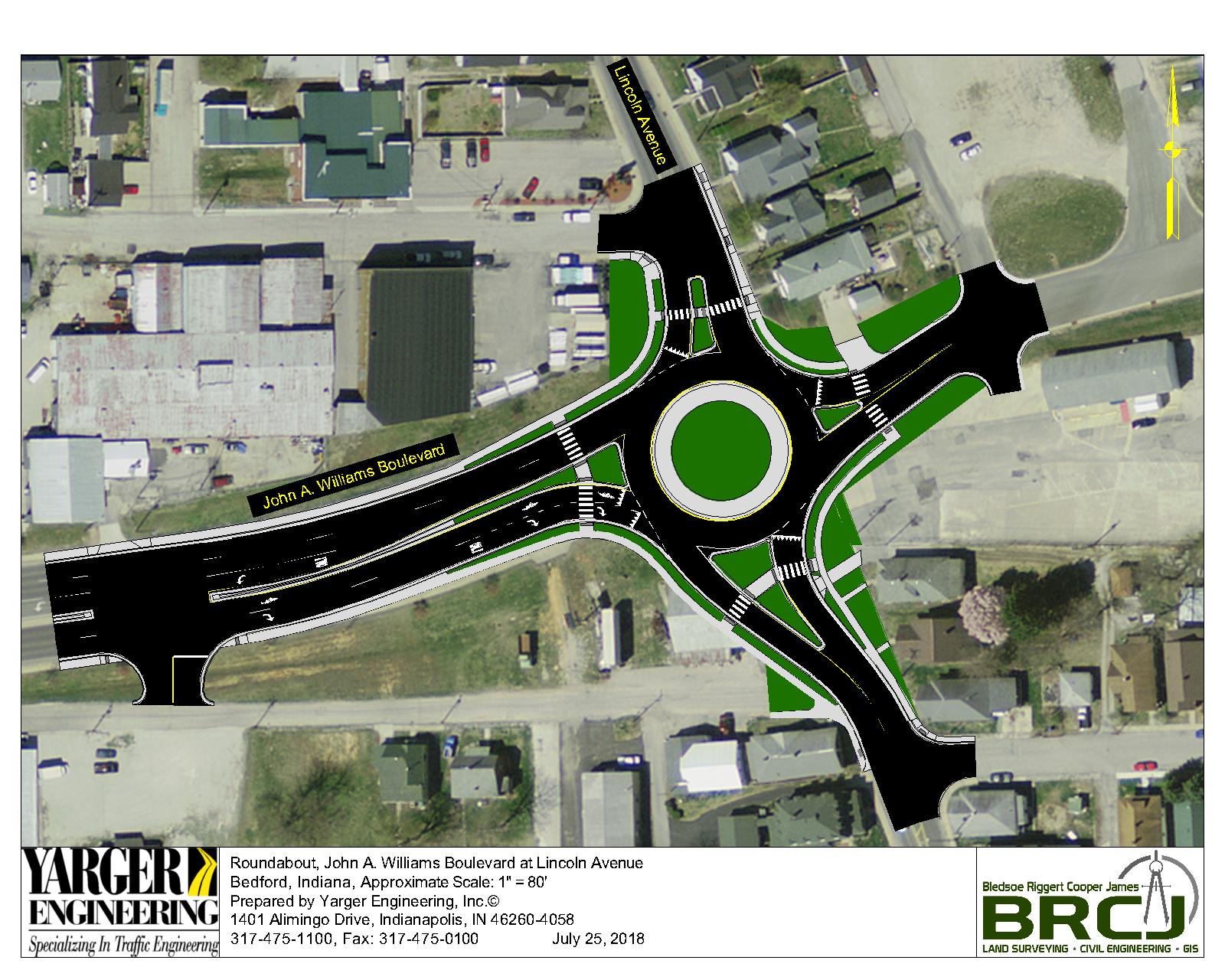

John A. Williams Boulevard at Lincoln Avenue, Bedford, Indiana 47421

Download Powerpoint Presentation for Williams at Lincoln Roundabout in Bedford, Indiana.Download Bedford Roundabout Figure

Call us at 317-475-1100 or email us today!

317-475-1100

317-475-1100 bwyarger@yargerengineering.com

bwyarger@yargerengineering.com